System innovation for a more sustainable leather chemistry

In short:

- In order to change the global leather supply chains a system view is necessary.

- A multi-stakeholder scenario process with industry, NGOs and academia resulted in a scenario story creating a shared positive vision for leather chemistry in 2035.

- Strategy workshops and a “Theory of Change” facilitated identification of specific steps to take in order to move towards the described scenario.

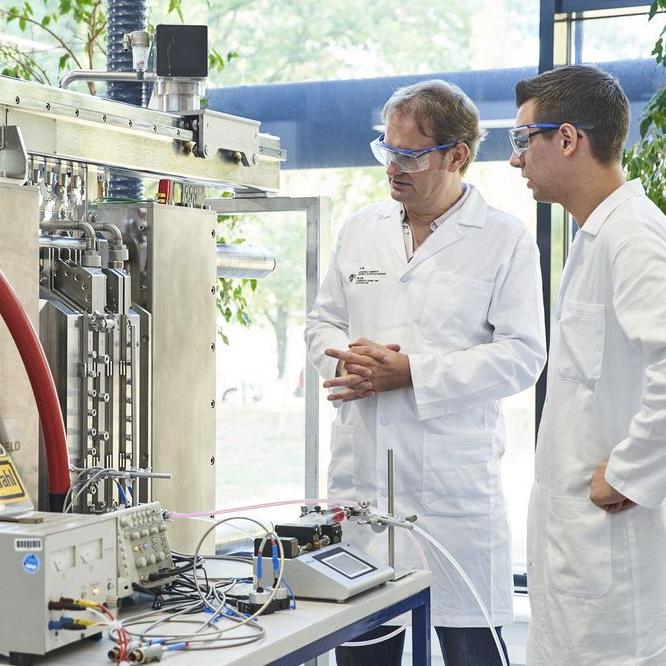

When it comes to achieving a "more sustainable chemistry" in the leather supply chains, the industry faces complex challenges. To overcome them, technical innovations - e.g. new bio-based tanning chemicals, optimized process flows - alone are not sufficient. The incentive situation of the actors in the global context must be analysed in order to apply these technologies. In addition, questions regarding the management of supply chains are crucial. This shows that forcing and, for example, contractual obligations only have a limited effect in ensuring that suppliers use chemicals defined by the customer in accordance with specific lists of requirements.

Innovative forms of collaboration along the supply chain seem to be essential. A certain degree of formalization of the new rules is required as well, whether through private governance initiatives by the industry or standardization or legislative activities. This triad of technical, social or organisational and institutional innovations shows the different relevant perspectives of a "system innovation". A systemic approach is also required for the transformation towards a more sustainable chemistry in the leather supply chains. The leather project of the Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences is based on this fundamental understanding. The project works at the current state of scientific research in the context of transformation research.

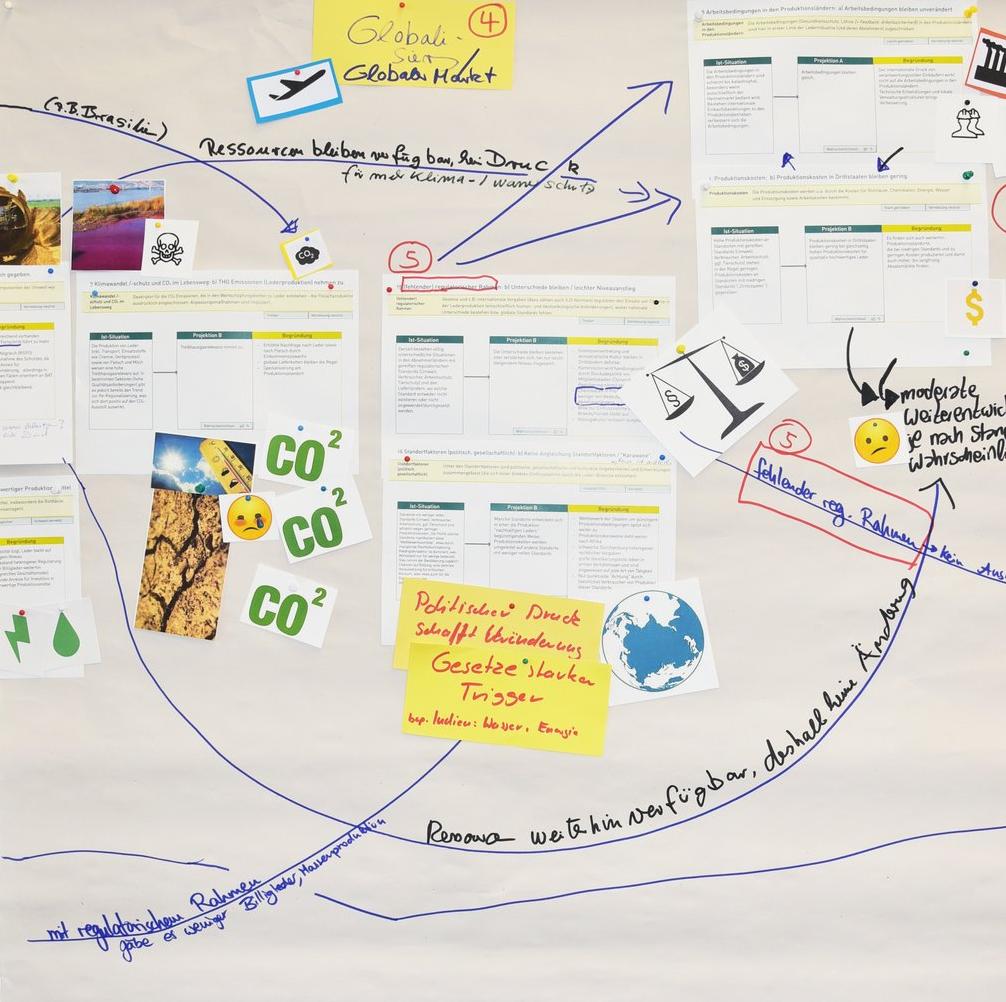

System view and vision development with the scenario technique

On the road to system innovation, a shared understanding of the challenges we face and, from this, the development of a common vision is essential. In October 2018, a workshop was held in Darmstadt with representatives along the leather supply chain (chemicals, tanning companies, processing industry, trade) and other stakeholders such as NGOs and political consultants (including Südwind, Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit/GIZ). The actors decided to use the Geschka scenario technique for this purpose, originally conceived as a method of strategic corporate planning. The university has already successfully applied this method in a similar project with the textile industry. A scenario team consisting of actors from the leather industry and other stakeholders was created, supported by the University of Applied Sciences Darmstadt, the project partner Schader Foundation and the management consultancy Geschka & Partner.

Between March and June 2019, the team developed future scenarios on "Leather 2035" with regard to the use and handling of chemicals in global supply chains. They first identified the 16 most important influencing factors (e.g. legal framework, transparency, process innovation) for the topic and evaluated their impact relationships. In the next step projections were developed, i.e. development perspectives for the influencing factors (e.g. in 2035 the legal framework for leather production will be more harmonised internationally), and to assess whether the projections are consistent with each other (i.e. do projected developments exclude each other, do they support each other etc.). In a further step, supported by a specialised analysis software, existing projections were compiled into "Leather 2035" scenarios based on this data. As a result of the scenario process two contrasting, yet consistent, scenario stories: "Muddling through" (scenario A) and "Boldly ahead" (scenario B) were developed.

Scenario A

Under the given global conditions, i.e. a growing demand for affordable leather, which under the existing cost pressure allows only a standardized, cost-optimized mass product, the leather industry in 2035 will be dominated by homogeneous "cheap" mass products, which at the same time have low requirements regarding functionality and quality of the leather.

Developing strategies with representatives of the entire supply chain

The members of the scenario team decided together to act appropriately to ensure that the developments described in scenario B take place. The h_da supports this implementation phase. In September and November 2019, strategy workshops were organized in Darmstadt and Frankfurt with the actors from the Scenario Team and other representatives from industry, trade, political consultancy and NGOs. The initial question of the workshop in September was which strategies and specific measures are necessary to initiate positive developments according to scenario story B ("Boldly ahead"). In working groups, the participants discussed the central questions raised by the scenario story, for example: How can transparency and traceability be implemented under competitive conditions? How can standards (working conditions, chemicals management etc.) be harmonised, controlled, sanctioned and implemented? The participants developed strategic approaches to these and two other questions in the context of "roadmaps": With the perspective up to 2035, consideringthe short-term perspective (up to 2022), they identified milestones that must be reached, formulated specific activities for each milestone and nominated actors for implementation. A second workshop in November was held to discuss the roadmaps again with other practitioners. The activities formulated in the roadmaps, individually or as a whole, already produced feasible ideas for sub-projects on the way to the scenario story.

Strategy for system innovation

The method of "Theory of Change" is a valuable tool for the design ("roadmap") and monitoring of system innovations. It makes it possible to capture individual steps and sub-measures and to examine them in a structured manner, taking into account the respective impact relationships. In the Theory of Change (ToC), activities and expected effects can be assigned to different spheres. Thus, the sphere of the direct project framework can be defined, as well as specific activities which take place within it (workshops, studies, etc.) and products created (technical innovations, policy advice, etc.). Only in this sphere, which is at the core of the ToC, the project participants have extensive control. The extent to which the field takes up these project results, i.e. actors adapt their behaviour in the direction of sustainable development, is the subject of further spheres around it. These are largely beyond the control of the project as the distance from the core increases. One of the reasons for this is that the intended impacts of a project often can only become apparent after its active duration and that the system is dependent on parallel developments that are not the subject of the project. Against this background, the ToC extends the perspective beyond the directly workable aspects of a project and includes parallel developments with a view to the overall goal orientation. In summary, the ToC takes on several functions, on the one hand by forming structures and pointing out systemic weaknesses in the project. The development of a ToC is based on an iterative process that reflects measures and projects relative to their effects and makes necessary upstream measures visible. On the other hand, it is suitable as a communication tool, as it clarifies complex transformation processes reduced to the essentials. Finally, it provides starting points for developing indicators for project performance. A theory of change for "more sustainable chemistry" in the leather supply chains is illustrated below (the ToC as PDF can be found here).

Target scenario for 2035: Process innovations have led to the production of high-quality leather everywhere in a way that saves natural resources. The markets for leather produced in this way are stable. The risks of chemicals in processes and products have largely been eliminated or are under control.

The normative impetus is accompanied by the political will to ensure the enforcement of legal requirements by means of appropriate enforcement measures. This is necessary if a high level of protection of human health and the environment is high on the political agenda at all locations. In addition, states should reward the commitment of companies that comply with their due diligence obligations.

If consumers are sensitised to and informed about the consequences of their consumption decisions, the probability that their consumption patterns will become more "sustainable" increases. In addition to the actual purchase decision, these include questions about care and maintenance, reuse and disposal of the goods. This is also associated with a change in the corresponding interest in information and demand behaviour.

Legislators around the world must take further action to ensure that supply chain players use "more sustainable chemistry" and meet further due diligence requirements. The European Union could be an important driving force in this respect. In 2020, it is preparing marketing restrictions for further chemicals (sensitizing substances in leather). At the same time, it is pursuing a strategic approach with the aim of a circular economy, which provides for concrete measures (tracking systems, product responsibility) to remove problematic chemicals from material flows. It would be necessary for legislators at all sites to harmonize the specifications for products and production processes at a demanding level. (Planned) legislation also acts as a driver for harmonisation activities in the leather industry.

Actors such as NGOs, the press, media and certain consumer groups will gain more knowledge about the use and handling of chemicals in the leather supply chains. On this basis, they can increase the pressure, both in consumer countries and at production sites, on companies and on legislators to ensure a "more sustainable chemistry".

Being able to trace chemicals in processes and products is a central component of "sustainable chemistry". This requires industry-wide communication standards (IT solutions, reporting obligations, etc.) to reduce the effort for suppliers (principle: enter data once, report to different customers several times) and to be able to focus on the quality of the data.

A "more sustainable chemistry" requires that actors cooperate better. This includes a more open approach to the issue of chemicals in processes and products: they no longer share only the indispensable minimum information, but communicate transparently in order to achieve their goals together. It is also important to address the incentives and obstacles faced by suppliers.

The actors at the production sites must acquire improved skills and opportunities in order to work towards a "more sustainable chemistry". This includes investment in production-side infrastructure and training. The use of new technologies and barrier-free didactic tools can also support the development of skills, especially for users with a low level of education.

Changed product development processes describe strategies that take into account central aspects of sustainable development as controlling factors in early phases of development and throughout the entire development process. Established standards and indicators for more sustainable production processes and products provide the base for these strategies. Linked to this is an iterative optimization process that continuously addresses questions of sourcing, working conditions, but also pollutants, methods of use and disposal options.

This refers to new or adapted sourcing strategies that pay particular attention to aspects of transparency and traceability as well as general criteria regarding the impact on humans and the environment. Ultimately, such purchasing behaviour in the supply chain leads to tenders and bids that already include aspects of sustainable development in the specification of raw materials and semi-finished products.